2/22/18 research article

primary dysmenorrhea in adolescents

pediatric forum Winter 2018

Menstrual cramps are the most common gynecologic symptom reported across all ages and ethnicities. Dysmenorrhea may affect upwards of 90 percent of women during their lifetime.1 It can result in school absenteeism, decreased social interactions with peers and withdrawal from sports participation, yet less than 15 percent of dysmenorrhea sufferers seek care from a medical provider for their symptoms. Most people have attempted home remedies and over-the-counter treatment options, which studies show have variable results.2

Primary dysmenorrhea is defined as pain with menstruation not attributable to pelvic pathology or abnormality. The onset of routine ovulation is thought to trigger the development of primary dysmenorrhea in adolescence. Secondary dysmenorrhea is due to a pelvic abnormality, such as endometriosis. Initiation of medical therapy should not be delayed while establishing a precise diagnosis as it is likely to alleviate symptoms for both primary and secondary dysmenor-rhea.3

diagnosis

The first step to treating primary dysmenorrhea is screening for menstrual health. The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) endorses the recommendations of the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology (ACOG) found in Committee Opinion No. 651, “Menstruation in Girls and Adolescents: Using the Menstrual Cycle as a Vital Sign.”

By engaging the patient and family in questions about menses, we open the discussion for when and what to expect with puberty and menarche. These conversations should start around age 7 or 8 years to be preparatory for the changes that come with puberty.

The median age for menarche in the United States is still 12.4 years. Typically, first menses occurs within two years of breast budding, and should be evaluated if not present within three years. Breast development is the first stage of puberty for females and can occur as young as 8 years old. On physical exam, menarche typically occurs once a patient reaches a sexual maturity rating (SMR) of four. Patients who have not started breast development by age 13 years, or have not reached menarche by age 15, should be referred for further evalua-tion.4

in adolescents

When patients present for a variety of concerns, incorporate questions about their menstrual history into your routine screening questions. Ask for the first day of the last menstrual period (LMP) with a year-at-a-glance calendar nearby when obtaining vital signs. A more thorough history should be obtained at least once a year to screen for the presence or absence of dysmenorrhea, any impact on school or lifestyle, the interval between periods, duration of bleeding and the amount of daily menstrual product use (Table 1). Any identified abnormalities can then be addressed in follow-up or referred for further investigation and treatment. Routine monitoring for menstrual health helps reinforce its importance to patients and families.

After progesterone levels decline, phospholipids are released from cell membranes. The fatty acids are converted to arachidonic acid (AA) by enzyme phospholipase A2. AA is then converted by cyclooxygenase into prostaglandins, then into leukotrienes via lipoxygenase. Prostaglandin F2-a (PGF2a) acts locally on the myometrium causing hypercontractility and vasoconstriction of the arterioles, leading to uterine ischemia and pain. Leukotrienes C4 and D4 have also been correlated with the severity and occurrence of menstrual pain. The actions of prostaglandins and leukotrienes are also responsible for the systemic symptoms of primary dysmenorrhea.5,6

Menstrual cramps typically present between 12 to 18 months after the first menstrual cycle with primary dysmenorrhea. While primary dysmenorrhea can present earlier than 12 months, the presence of dysmenorrhea at the onset of menarche should raise suspicion for an obstructing genital tract malformation. Primary dysmen-orrhea accounts for 90 percent of menstrual pain in adolescents. It is due to the physiologic response to progesterone withdrawal seen after involution of the corpus luteum.

Patients presenting with primary dysmenorrhea often complain of a colicky, lower abdominal pain starting with or close to the onset of menstrual bleeding and lasting up to 48 to 72 hours. Some individuals may report pain that starts one to two days before their period. Additionally, they may complain of associated headaches, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, back pain, fatigue and dizziness. Factors associated with the development of primary dysmenorrhea include age of menarche less than 12 years; first-hand and second-hand tobacco smoke exposure; a body mass index of less than 20; a history of long, heavy or irregular periods; and the presence of premenstrual symptoms.

The impact of dysmenor-rhea on involvement in activities, such as school, sports and social events, is an important indicator of severity and need for intervention. School absenteeism is more common with moderate to severe dysmenorrhea. Approximately 14 percent of adolescents with dys-menorrhea report missing two or more days a month due to pain. The use of analgesics should also be determined, with emphasis on dose and frequency, as many people do not use over-the-counter medications effectively. Individuals may have tried a variety of options, including supplements and complementary medicine, in an attempt to treat the pain.

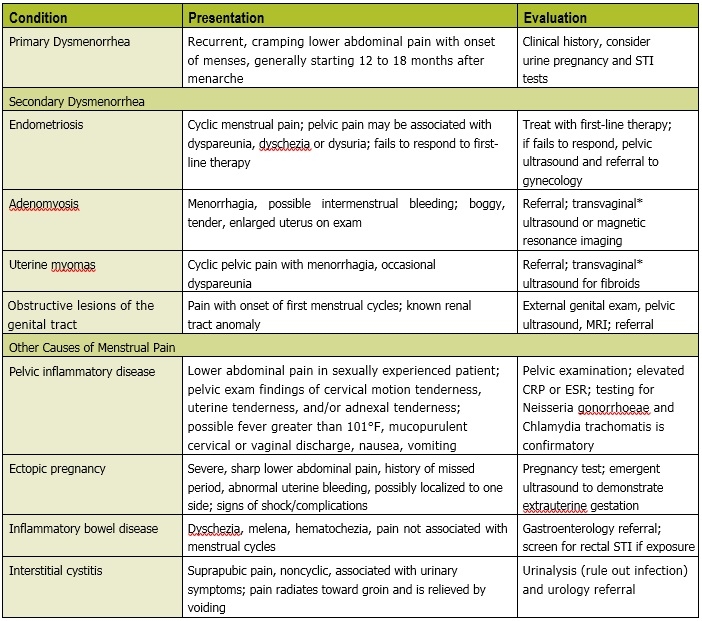

The differential for dysmen-orrhea includes gynecologic causes of secondary dysmenorrhea and non-gynecologic causes (Table 2). Endometriosis is the most common gynecologic cause of secondary dysmenorrhea and occurs more frequently in adolescents with a positive family history in a first-degree relative. Additional clues to differentiating primary and secondary dysmenorrhea include symptoms that are unresponsive to first-line therapy with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and hormonal therapy; new onset of symptoms in a sexually active adolescent; atypical pain symptoms of dysuria, dyschezia or dyspareunia; or pelvic pain unrelated to the menstrual cycle. Patients with known renal tract abnormalities may have underlying Müllerian anomalies that present as dysmenorrhea with the first menstrual cycle.

Part of a thorough history for dysmenorrhea includes inquiry into prior sexual behavior and safe sex or contraceptive practices. Ensuring confidentiality practices in your office can help youth feel more comfortable with disclosing their history. For some youth, dysmenorrhea may be an acceptable reason to obtain needed contraception. Screen for signs and symptoms of sexually transmitted infections or pelvic inflammatory disease, and perform a pelvic exam if necessary to rule out this cause of new onset pelvic pain.

The physical examination for primary dysmenorrhea should include an abdominal exam for any palpable abnormalities. For sexually naïve adolescents with a typical primary dysmenorrhea history, pelvic examination is not necessary for diagnosis. Consideration of an external genital exam should be made to rule out the presence of an abnormality of the hymen. However, if the history is suggestive of causes other than primary dysmenorrhea, or the patient is not responding to first-line therapy for primary dysmenorrhea, a pelvic examination is indicated.

Imaging and laboratory testing are not recommended for primary dysmenorrhea. Testing for pregnancy, N. gonorrhoeae and Chlamydia trachomatis are important in sexually active adolescents. Pelvic ultrasound should be used first when evaluating for pelvic anomalies as a cause of secondary dysmenorrhea, or if the patient has failed to respond to adequate therapy over three to six months. A transvaginal ultrasound is generally not recommended for patients with an intact hymen or prior to coitarche. In such cases, if the images cannot be obtained via transabdominal ultrasound, then magnetic resonance imaging may be recommended to avoid traumatizing the patient. A referral should be made to adolescent gynecology for patients suspected of secondary dysmenorrhea.

treatment

Treatment for dysmenorrhea should take into consideration what methods the patient has previously tried since many strategies are available over the counter. Non-pharmacologic methods including exercise, yoga, dietary modification and acupuncture have been investigated, but the results are conflicting from small studies. Topical heat has been shown to provide symptomatic relief of pain and is an inexpensive, easily accessed option. A variety of supplemental herbs and vitamins such as ginger, fish oil, vitamin B1 or rosehips may be used by some patients. A Cochrane review from 2016 of dietary supplements for dysmenorrhea (27 studies, 3,101 women) found a lack of high-quality evidence to support recommendations for use.7

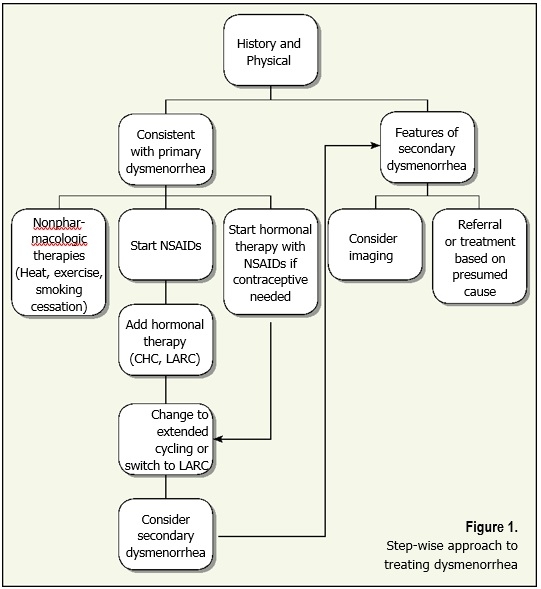

Pharmacologic management of dysmenorrhea is step-wise and should consider additional benefits and contraceptive needs.

First-line treatment options include NSAIDs, combined hormonal therapy and long-acting reversible contraceptives (LARCs). The goal of pharmacologic treatment is to reduce prostaglandin production and action, as well as menstrual flow.

ϒ – For use in women older than 18 years

NSAIDs work to inhibit the cyclooxygenase pathway preventing the production of PGF2a from arachidonic acid. A recent Cochrane review of 80 randomized controlled trials concluded that NSAIDs are superior to placebo in the treatment of dysmenorrhea. There is not enough evidence to recommend one NSAID over another.8 When choosing NSAIDs, consideration should be made for ease of use and adherence to dosing recommendations. NSAIDs should be started one to two days prior to the onset of menses if the cycle is predictable, or immediately with onset if it is not predictable. Scheduled dosing should continue for the first two to three days of the menstrual cycle. Use of a loading dose has been shown to have some improvement over pain control (Table 3).

Combined hormonal therapy (CHC) in the form of the contraceptive vaginal ring, the transdermal contraceptive patch and oral contraceptive pills (OCP), provide benefit by suppressing monthly ovulation and limiting endometrial growth. These actions thereby reduce the production and release of prostaglandins and leukotrienes. Low-dose OCP (20 mcg ethinyl estradiol and 100 mg levonorgestrel) has been found to effectively reduce dysmenorrhea symptoms in adolescents. Small studies, mostly in adult women, have shown more improvement in pain symptom reduction with OCPs or the vaginal ring (ethinyl estradiol and etonogestrel) than the transdermal patch (20 mcg ethinyl estradiol and 150 mcg norelgestromin daily). Additionally, the use of extended cycling to reduce the number of hormone-free days has been shown to decrease the frequency of dysmenorrhea.

Depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (DMPA) is another option available, but requires injections every 11-13 weeks and has a potential side effect of weight gain most adolescents find unacceptable. Concerns about reduction in bone mineral density accumulation during adolescence with prolonged use of DMPA should be reviewed with the patient and/or family.

LARCs include the levonorgestrel intrauterine device (LNG-IUD) and the subdermal single rod etonogestrel implant. The mechanism of benefit for dysmenorrhea with the LNG-IUD is mainly local action on the endometrium to reduce endometrial development and growth. The implant reduces dysmenorrhea through inhibiting ovulation with sufficiently elevated progestin levels. These methods are effective for years and provide a reliable, highly effective contraceptive benefit. Training to provide these services in your office is available, or referral to a skilled provider is needed for placement and surveillance of LARCs.

Conclusion

Screening for the presence of dysmenorrhea provides an opportunity to improve the quality of life and level of functioning for your adolescent patients. The prevalence of dysmenorrhea in adolescents is reported as high as 93 percent (range 48 percent to 93 percent), causing many people to believe it is an inevitable part of menstruation. Incorporating a menstrual history into office visits opens the discussion for health prevention and treatment before unnecessary negative effects on sports, school and home. A step-wise approach to dysmenorrhea treatment makes it manageable for both patient and provider.

view entire Winter 2018 pediatric forum

references

- Osayande AS, Mehulic S. Diagnosis and initial management of dysmenorrhea. Am Fam Physician. 2014;89(5):341-346.

-

Allen LM, Lam AC. Premenstrual syndrome and dysmenorrhea in adolescents. Adolesc Med State Art Rev. 2012;23(1):139-163.

-

Burnett M, Lemyre M. No. 345-primary dysmenor-rhea consensus guideline. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2017;39(7):585-595.

-

ACOG Committee opinion no. 651: Menstruationin girls and adolescents: Using the menstrual cycle as a vital sign. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;126(6):e143-6.

- De Sanctis V, Soliman A, Bernasconi S, et al. Primary dysmenorrhea in adolescents: Prevalence, impact and recent knowledge. Ped Endocrinol Rev. 2015;13(2):512-520.

-

Sultan C, Gaspari L, Paris F. Adolescent dysmenor-rhea. In: Sultan C, ed. Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology: Evidence-Based Clinical Practice. 2nd rev ed. Basel, Switzerland: Karger; 2012:171-180.

-

Pattanittum P, Kunyanone N, Brown J, et al. Dietary supplements for dysmenorrhoea. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;3:CD002124. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD002124.pub2.

-

Marjoribanks J, Ayeleke RO, Farquhar C, Proctor M. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for dysmenorrhoea. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;7:CD001751. doi:10.1002/14651858. CD001751.pub3.